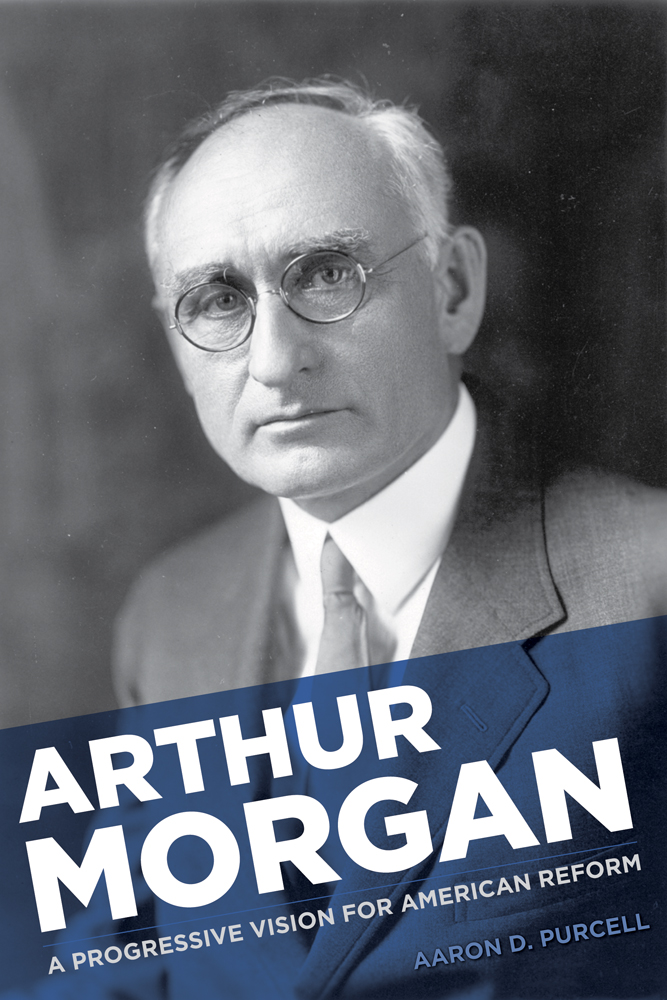

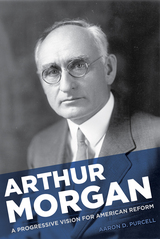

Arthur Morgan: A Progressive Vision for American Reform

University of Tennessee Press, 2014

Cloth: 978-1-62190-058-0 | eISBN: 978-1-62190-129-7

Library of Congress Classification E748.H78 2014

Dewey Decimal Classification 370.92

Cloth: 978-1-62190-058-0 | eISBN: 978-1-62190-129-7

Library of Congress Classification E748.H78 2014

Dewey Decimal Classification 370.92

ABOUT THIS BOOK | AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY | TOC | REQUEST ACCESSIBLE FILE

ABOUT THIS BOOK

On May 19, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced the appointment of Arthur Morgan (1878–1975), a water-control engineer and college president from Ohio, as the chairman of the newly created Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). With the eyes of the nation focused on the reform and recovery promised by the New Deal, Morgan remained in the national spotlight for much of the 1930s, as his visionary plans for the TVA drew both support and criticism. In this thoughtful biography, Aaron D. Purcell re-assesses Morgan’s long life and career and provides the first detailed account of his post-TVA activities and fascination with utopian writer Edward Bellamy. As Purcell demonstrates, Morgan embraced an alternative type of Progressive Era reform throughout his life which was rooted in nineteenth-century socialism, an overlooked, but important, strain in American political thought.

Purcell pinpoints Morgan’s reading of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward while a teenager as a watershed moment in the development of his vision for building modern American society. He recounts Morgan’s early successes as an engineer, budding Progressive leader, and educational reformer; his presidency of Antioch College; and his revolutionary but contentious tenure at the TVA. After his dismissal from the TVA, Morgan wrote extensively, eventually publishing over a dozen books, including a biography of Edward Bellamy, and countless articles. He also raised money to support an experimental community in Kerala, India, sharing Mahatma Gandhi’s belief in small, self-sustaining communities cooperatively supported by persons of strong moral character. At the same time, however, Morgan retained many of his late-nineteenth century beliefs, including eugenics, as part of his societal vision. His authoritarian administrative style and moral rigidity limited his ability to attract large numbers to his community-based vision.

As Purcell demonstrates, Morgan remained an active reformer well into the second half of the twentieth century, carrying forward a vision for American reform decades after his Progressive Era contemporaries had faded into obscurity. By presenting Morgan’s life and career within the context of the larger social and cultural events of his day, this revealing biographical study offers new insight into the achievements and motivations of an important but historically neglected American reformer.

Purcell pinpoints Morgan’s reading of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward while a teenager as a watershed moment in the development of his vision for building modern American society. He recounts Morgan’s early successes as an engineer, budding Progressive leader, and educational reformer; his presidency of Antioch College; and his revolutionary but contentious tenure at the TVA. After his dismissal from the TVA, Morgan wrote extensively, eventually publishing over a dozen books, including a biography of Edward Bellamy, and countless articles. He also raised money to support an experimental community in Kerala, India, sharing Mahatma Gandhi’s belief in small, self-sustaining communities cooperatively supported by persons of strong moral character. At the same time, however, Morgan retained many of his late-nineteenth century beliefs, including eugenics, as part of his societal vision. His authoritarian administrative style and moral rigidity limited his ability to attract large numbers to his community-based vision.

As Purcell demonstrates, Morgan remained an active reformer well into the second half of the twentieth century, carrying forward a vision for American reform decades after his Progressive Era contemporaries had faded into obscurity. By presenting Morgan’s life and career within the context of the larger social and cultural events of his day, this revealing biographical study offers new insight into the achievements and motivations of an important but historically neglected American reformer.

See other books on: Bellamy, Edward | Community development | Educators | Social reformers | Tennessee Valley Authority

See other titles from University of Tennessee Press