44 start with A start with A

A comprehensive history of abortion in Renaissance Italy.

In this authoritative history, John Christopoulos provides a provocative and far-reaching account of abortion in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy. His poignant portraits of women who terminated or were forced to terminate pregnancies offer a corrective to longstanding views: he finds that Italians maintained a fundamental ambivalence about abortion. Italians from all levels of society sought, had, and participated in abortions. Early modern Italy was not an absolute anti-abortion culture, an exemplary Catholic society centered on the “traditional family.” Rather, Christopoulos shows, Italians held many views on abortion, and their responses to its practice varied.

Bringing together medical, religious, and legal perspectives alongside a social and cultural history of sexuality, reproduction, and the family, Christopoulos offers a nuanced and convincing account of the meanings Italians ascribed to abortion and shows how prevailing ideas about the practice were spread, modified, and challenged. Christopoulos begins by introducing readers to prevailing ideas about abortion and women’s bodies, describing the widely available purgative medicines and surgeries that various healers and women themselves employed to terminate pregnancies. He then explores how these ideas and practices ran up against and shaped theology, medicine, and law. Catholic understanding of abortion was changing amid religious, legal, and scientific debates concerning the nature of human life, women’s bodies, and sexual politics. Christopoulos examines how ecclesiastical, secular, and medical authorities sought to regulate abortion, and how tribunals investigated and punished its procurers—or did not, even when they could have. Abortion in Early Modern Italy offers a compelling and sensitive study of abortion in a time of dramatic religious, scientific, and social change.

The terms “capitalism” and “socialism” continue to haunt our political and economic imaginations, but we rarely consider their interconnected early history. Even the eighteenth century had its “socialists,” but unlike those of the nineteenth, they paradoxically sought to make the world safe for “capitalists.” The word “socialists” was first used in Northern Italy as a term of contempt for the political economists and legal reformers Pietro Verri and Cesare Beccaria, author of the epochal On Crimes and Punishments. Yet the views and concerns of these first socialists, developed inside a pugnacious intellectual coterie dubbed the Academy of Fisticuffs, differ dramatically from those of the socialists that followed.

Sophus Reinert turns to Milan in the late 1700s to recover the Academy’s ideas and the policies they informed. At the core of their preoccupations lay the often lethal tension among states, markets, and human welfare in an era when the three were becoming increasingly intertwined. What distinguished these thinkers was their articulation of a secular basis for social organization, rooted in commerce, and their insistence that political economy trumped theology as the underpinning for peace and prosperity within and among nations.

Reinert argues that the Italian Enlightenment, no less than the Scottish, was central to the emergence of political economy and the project of creating market societies. By reconstructing ideas in their historical contexts, he addresses motivations and contingencies at the very foundations of modernity.

Over the past thirty years, Italy—the historic home of Catholicism—has become a significant destination for migrants from Nigeria and Ghana. Along with suitcases and dreams of a brighter future, these Africans bring their own form of Christianity, Pentecostalism, shaped by their various cultures and religious worlds. At the heart of Annalisa Butticci’s beautifully sculpted ethnography of African Pentecostalism in Italy is a paradox. Pentecostalism, traditionally one of the most Protestant of Christian faiths, is driven by the same concern as Catholicism: real presence.

In Italy, Pentecostals face harsh anti-immigrant sentiment and limited access to economic and social resources. At times, they find safe spaces to worship in Catholic churches, where a fascinating encounter unfolds that is equal parts conflict and communion. When Pentecostals watch Catholics engage with sacramental objects—relics, statues, works of art—they recognize the signs of what they consider the idolatrous religions of their ancestors. Catholics, in turn, view Pentecostal practices as a mix of African religions and Christian traditions. Yet despite their apparently irreconcilable differences and conflicts, they both share a deeply sensuous and material way to make the divine visible and tangible. In this sense, Pentecostalism appears much closer to Catholicism than to mainstream Protestantism.

African Pentecostals in Catholic Europe offers an intimate glimpse at what happens when the world’s two fastest growing Christian faiths come into contact, share worship space, and use analogous sacramental objects and images. And it explains how their seemingly antithetical practices and beliefs undergird a profound commonality.

Fabio Parasecoli discovers that for centuries, southern Mediterranean countries such as Italy fought against food scarcity, wars, invasions, and an unfavorable agricultural environment. Lacking in meat and dairy, Italy developed foodways that depended on grains, legumes, and vegetables until a stronger economy in the late 1950s allowed the majority of Italians to afford a more diverse diet. Parasecoli elucidates how the last half century has seen new packaging, conservation techniques, industrial mass production, and more sophisticated systems of transportation and distribution, bringing about profound changes in how the country’s population thought about food. He also reveals that much of Italy’s culinary reputation hinged on the world’s discovery of it as a healthy eating model, which has led to the prevalence of high-end Italian restaurants in major cities around the globe.

Including historical recipes for delicious Italian dishes to enjoy alongside a glass of crisp Chianti, Al Dente is a fascinating survey of this country’s cuisine that sheds new light on why we should always leave the gun and take the cannoli.

Aldo Moro’s kidnapping and violent death in 1978 shocked Italy as no other event has during the entire history of the Republic. It had much the same effect in Italy as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy had in the United States, with both cases giving rise to endless conspiracy theories. The dominant Christian Democratic leader for twenty years, Moro had embodied the country’s peculiar religious politics, its values as well as its practices. He was perceived as the most exemplary representative of the Catholic political tradition in Italy. The Red Brigades who killed him thought that in striking Moro they would cause the collapse of the capitalist establishment and clear the way for a Marxist-Leninist revolution.

In his thorough account of the long and anguished quest for justice in the Moro murder case, Richard Drake provides a detailed portrait of the tragedy and its aftermath as complex symbols of a turbulent age in Italian history. Since Moro’s murder, documents from two parliamentary inquiries and four sets of trials explain the historical and political process and illuminate two enduring themes in Italian history. First, the records contain a wealth of examples bearing on the nation’s longstanding culture of ideological extremism and violence. Second, Moro’s story reveals much about the inner workings of democracy Italian style, including the roles of the United States and the Mafia. These insights are especially valuable today in understanding why the Italian establishment is in a state of collapse.

The Moro case also explores the worldwide problem of terrorism. In great detail, the case reveals the mentality, the tactics, and the strategy of the Red Brigades and related groups. Moro’s fate has a universal poignancy, with aspects of a classical Greek tragedy. Drake provides a full historical account of how the Italian people have come to terms with this tragedy.

Aldus Manutius is perhaps the greatest figure in the history of the printed book: in Venice, Europe’s capital of printing, he invented the italic type and issued more first editions of the classics than anyone before or since, as well as Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, the most beautiful and mysterious printed book of the Italian Renaissance.

This is the first monograph in English on Aldus Manutius in over forty years. It shows how Aldus redefined the role of a book printer, from mere manual laborer to a learned publisher. As a consequence, Aldus participated in the same debates as contemporaries such as Leonardo da Vinci and Erasmus of Rotterdam, making this book an insight into their world too.

Taking as a starting point the Italian crisis over immigration in the early 1990s, Merrill examines grassroots interethnic spatial politics among female migrants and Turin feminists in Northern Italy. Using rich ethnographic material, she traces the emergence of Alma Mater—an anti-racist organization formed to address problems encountered by migrant women. Through this analysis, Merrill reveals the dynamics of an alliance consisting of women from many countries of origin and religious and class backgrounds.

Highlighting an interdisciplinary approach to migration and the instability of group identities in contemporary Italy, An Alliance of Women presents migrants grappling with spatialized boundaries amid growing nativist and anti-immigrant sentiment in Western Europe.

Heather Merrill is assistant professor of geography and anthropology at Dickinson College.

An American Social Worker in Italy was first published in 1961. Minnesota Archive Editions uses digital technology to make long-unavailable books once again accessible, and are published unaltered from the original University of Minnesota Press editions.

Mrs. Charnley, an American social worker, spent six months in Italy on a Fulbright grant as a consultant to Italian child welfare agencies and schools of social work. Here, in diary form, she tells of her experiences during those months when she struggled to teach American social work principles to her Italian colleagues. The task was complicated not only by the need to communicate in a newly learned tongue but also by the necessity to tailor American casework philosophies to a vastly different culture. The story abounds in humor and pathos and, at the same time, offers rich information about Italy, its people, and its child-care methods and institutions.

Mrs. Charnley points out that one Italian child in ten spends his first seventeen years in an institution. The nation's laws for the protection of children date back to the Caesars; even the most progressive of the social workers she met hoped for reforms only in terms of decades or centuries. Against this background, the situations in which she found herself were sometimes frustrating, often comic, always challenging. Her determination to help Italy's half-million institutionalized children took her behind the doors of many orphanages and convents, into close contact with the children and the nuns and priests who cared for them. She studied the records of social agencies, analyzed problems with their staffs, and lectured at social work schools.

Born in Australia, Shirley Hazzard first moved to Naples as a young woman in the 1950s to take up a job with the United Nations. It was the beginning of a long love affair with the city. The Ancient Shore collects the best of Hazzard’s writings on Naples, along with a classic New Yorker essay by her late husband, Francis Steegmuller. For the pair, both insatiable readers, the Naples of Pliny, Gibbon, and Auden is constantly alive to them in the present.

With Hazzard as our guide, we encounter Henry James, Oscar Wilde, and of course Goethe, but Hazzard’s concern is primarily with the Naples of our own time—often violently unforgiving to innocent tourists, but able to transport the visitor who attends patiently to its rhythms and history. A town shadowed by both the symbol and the reality of Vesuvius can never fail to acknowledge the essential precariousness of life—nor, as the lover of Naples discovers, the human compassion, generosity, and friendship that are necessary to sustain it.

Beautifully illustrated by photographs from such masters as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Herbert List, The Ancient Shore is a lyrical letter to a lifelong love: honest and clear-eyed, yet still fervently, endlessly enchanted.

“Much larger than all its parts, this book does full justice to a place, and a time, where ‘nothing was pristine, except the light.’”—Bookforum

“Deep in the spell of Italy, Hazzard parses the difference between visiting and living and working in a foreign country. She writes with enormous eloquence and passion of the beauty of getting lost in a place.”—Susan Slater Reynolds, Los Angeles Times

“The two voices join in exquisite harmony. . . . A lovely book.”—Booklist, starred review

Reflecting the Getty's commitment to open content, Ancient Terracottas from South Italy and Sicily in the J. Paul Getty Museum is available online at www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas and may be downloaded for free.

Through careful and detailed archival research, Spencer creates a fascinating portrait of Castagno’s patronage as a web, at the center of which was Cosimo de’ Medici, who constituted the focal point of a network of business partnerships, real estate transactions, loans, and special privileges in which the artist’s patrons were enmeshed. The author constructs partial biographies of unknown and lesser-known patrons to show the relation of these patrons to each other and to the artist, demonstrating the degree to which artistic production in Renaissance Italy was tied to politics and economics.

Spencer discusses each of Castagno’s extant and some of his lost paintings, dating the works with greater accuracy than ever before. His understanding of the patrons and of the motivations behind the commissions makes it possible for Spencer to bring new interpretations to many of these works. This book offers a deeper understanding of a particular artist’s life and work while also exploring the larger question of the unique relationship between private patrons and independent artists in the Italian Renaissance.

The Other Voice in Early Modern Women: The Toronto Series volume 70

First brought to Florence by Lorenzo de’ Medici as a celebrity preacher, Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498), a Dominican friar, would ultimately play a major role in the events that convulsed the city in the 1490s and led to the overthrow of the Medici themselves. After a period when he held close to absolute power in the great Renaissance republic, Savonarola was excommunicated by the Borgia pope, Alexander VI, in 1497 and, after a further year of struggle, was hanged and burned in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria in 1498.

The Latin writings brought together in this volume consist of various letters, a formal apologia, and his Dialogue on the Truth of Prophecy, all written in the last year of his life. They defend his prophetic mission and work of reform in Florence while providing a fascinating window onto the mind of a religious fanatic. All these works are here translated into English for the first time.

One of the most controversial questions in Italy today concerns the origins of the political terror that ravaged the country from 1969 to 1984, when the Red Brigades, a Marxist revolutionary organization, intimidated, maimed, and murdered on a wide scale.

In this timely study of the ways in which an ideology of terror becomes rooted in society, Richard Drake explains the historical character of the revolutionary tradition to which so many ordinary Italians professed allegiance, examining its origins and internal tensions, the men who shaped it, and its impact and legacy in Italy. He illuminates the defining figures who grounded the revolutionary tradition, including Carlo Cafiero, Antonio Labriola, Benito Mussolini, and Antonio Gramsci, and explores the connections between the social disasters of Italy, particularly in the south, and the country's intellectual politics; the brand of "anarchist communism" that surfaced; and the role of violence in the ideology. Though arising from a legitimate sense of moral outrage at desperate conditions, the ideology failed to find the political institutions and ethical values that would end inequalities created by capitalism.

In a chilling coda, Drake recounts the recent murders of the economists Massimo D'Antona and Marco Biagi by the new Red Brigades, whose Internet justification for the killings is steeped in the Marxist revolutionary tradition.

The Roman poet Statius called the via Appia “the Queen of Roads,” and for nearly a thousand years that description held true, as countless travelers trod its path from the center of Rome to the heel of Italy. Today, the road is all but gone, destroyed by time, neglect, and the incursions of modernity; to travel the Appian Way today is to be a seeker, and to walk in the footsteps of ghosts.

Our guide to those ghosts—and the layers of history they represent—is Robert A. Kaster. In The Appian Way, he brings a lifetime of studying Roman literature and history to his adventures along the ancient highway. A footsore Roman soldier pushing the imperial power south; craftsmen and farmers bringing their goods to the towns that lined the road; pious pilgrims headed to Jerusalem, using stage-by-stage directions we can still follow—all come to life once more as Kaster walks (and drives—and suffers car trouble) on what’s left of the Appian Way. Other voices help him tell the story: Cicero, Goethe, Hawthorne, Dickens, James, and even Monty Python offer commentary, insight, and curmudgeonly grumbles, their voices blending like the ages of the road to create a telescopic, perhaps kaleidoscopic, view of present and past.

To stand on the remnants of the Via Appia today is to stand in the pathway of history. With The Appian Way, Kaster invites us to close our eyes and walk with him back in time, to the campaigns of Garibaldi, the revolt of Spartacus, and the glory days of Imperial Rome. No traveler will want to miss this fascinating journey.

Fabretti's treatise, De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae dissertationes tres, is cited as a matter of course by all later scholars working in the area of Roman topography. Its findings--while updated and supplemented by more recent archaeological efforts--have never been fully superseded. Yet despite its enormous importance and impact on scholarly efforts, the De aquis has never yet been translated from the original Latin. Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century provides a full translation of and commentary on Fabretti's writings, making them accessible to a broad audience and carefully assessing their scholarly contributions.

Harry B. Evans offers his reader an introduction to Fabretti and his scholarly world. A complete translation and a commentary that focuses primarily on the topographical problems and Fabretti's contribution to our understanding of them are also provided. Evans also assesses the contributions and corrections of later archaeologists and topographers and places the De aquis in the history of aqueduct studies.

Evans demonstrates that Fabretti's conclusions, while far from definitive, are indeed significant and merit wider attention than they have received to date. This book will appeal to classicists and classical archaeologists, ancient historians, and readers interested in the history of technology, archaeology, and Rome and Italy in the seventeenth century.

Harry B. Evans is Professor of Classics, Fordham University.

In this amply illustrated volume, John Beldon Scott traces the history of the unique relic, focusing especially on the black-marble and gilt-bronze structure Guarino Guarini designed to house and exhibit it. A key Baroque monument, the chapel comprises many unusual architectural features, which Scott identifies and explains, particulary how the chapel's unprecedented geometry and bizarre imagery convey to the viewer the supernatural powers of the object enshrined there. Drawing on early plans and documents, he demonstrates how the architect's design mirrors the Shroud's strange history as well as political aspirations of its owners, the Dukes of Savoy. Exhibiting it ritually, the Savoy prized their relic with its godly vestige as a means to link their dynasty with divine purposes. Guarini, too, promoted this end by fashioning an illusionary world and sacred space that positioned the duke visually so that he appeared close to the Shroud during its ceremonial display. Finally, Scott describes how the additional need for an outdoor stage for the public showing of the relic to the thousands who came to Turin to see it also helped shape the urban plan of the city and its transformation into the Savoyard capital.

Exploring the mystique of this enigmatic relic and investigating its architectural and urban history for the first time, Architecture for the Shroud will appeal to anyone curious about the textile, its display, and the architectural settings designed to enhance its veneration and boost the political agenda of the ruling family.

Through autobiographical sketches, theoretical essays, interviews, and conversations with such luminaries as Jean-Luc Godard and Alberto Moravia, this compelling volume explores the director’s unique brand of narrative-defying cinema as well as the motivations and anxieties of the man behind the camera.

“The Architecture of Vision provides a filmmaker’s absorbing reflections and insights on his career. . . . Antonioni’s comments . . . deepen and humanize a sometimes cerebral book.”—Publishers Weekly

“[Antonioni’s] erudition is astonishing . . . few of his peers can match his verbal articulateness.”—Film Quarterly

“This valuable resource offers entrée to material difficult to gain access to under other circumstances.”—Library Journal

Arms and the Woman: Classical Tradition and Women Writers in the Venetian Renaissance by Francesca D’Alessandro Behr focuses on the classical reception in the works of female authors active in Venice during the Early Modern Age. Even in this relatively liberal city, women had restricted access to education and were subject to deep-seated cultural prejudices, but those who read and wrote were able, in part, to overcome those limitations.

In this study, Behr explores the work of Moderata Fonte and Lucrezia Marinella and demonstrates how they used knowledge of texts by Virgil, Ovid, and Aristotle to systematically reanalyze the biased patterns apparent both in the romance epic genre and contemporary society. Whereas these classical texts were normally used to bolster the belief in female inferiority and the status quo, Fonte and Marinella used them to envision societies structured according to new, egalitarian ethics. Reflecting on the humanist representation of virtue, Fonte and Marinella insisted on the importance of peace, mercy, and education for women. These authors took up the theme of the equality of genders and participated in the Renaissance querelle des femmes, promoting women’s capabilities and nature.

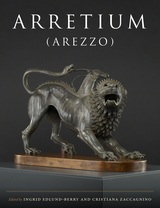

A comprehensive examination of the history and excavation of the Etruscan city of Arretium.

Beneath the Italian city of Arezzo lie the remains of Etruscan Arretium. This volume, the first comprehensive treatment of excavations at Arretium, gathers the most up-to-date scholarship on the city and delves into key archaeological discoveries and the stories they tell about life in the Etruscan world.

Chapters explore local history—including the city’s complex political exchanges with Rome—Etruscan religion, Arretium’s role as a center of the arts, and the challenges of excavation amid the bustle of European urban modernity. Editors Ingrid Edlund-Berry and Cristiana Zaccagnino have gathered chapters by expert contributors that detail Arretium’s material culture, including the city’s famed pottery, Arretine ware, which was known across the Mediterranean; terracotta pieces depicting gods and other supernatural beings; and exquisite bronze-work, most notably the piece now known as the Chimaera of Arezzo. One of the few Etruscan cities that continued flourishing after the Roman takeover, Arretium proves to be a trove of archaeological riches and of the historical insights they reveal.

“In Naples, there are more singers than there are unemployed people.” These words echo through the neomelodica music scene, a vast undocumented economy animated by wedding singers, pirate TV, and tens of thousands of fans throughout southern Italy and beyond. In a city with chronic unemployment, this setting has attracted hundreds of aspiring singers trying to make a living—or even a fortune. In the process, they brush up against affiliates of the region’s violent organized crime networks, the camorra. In The Art of Making Do in Naples, Jason Pine explores the murky neomelodica music scene and finds himself on uncertain ground.

The “art of making do” refers to the informal and sometimes illicit entrepreneurial tactics of some Neapolitans who are pursuing a better life for themselves and their families. In the neomelodica music scene, the art of making do involves operating do-it-yourself recording studios and performing at the private parties of crime bosses. It can also require associating with crime boss-impresarios who guarantee their success by underwriting it with extortion, drug trafficking, and territorial influence. Pine, likewise “making do,” gradually realized that the completion of his ethnographic work also depended on the aid of forbidding figures.

The Art of Making Do in Naples offers a riveting ethnography of the lives of men who seek personal sovereignty in a shadow economy dominated, in incalculable ways, by the camorra. Pine navigates situations suffused with secrecy, moral ambiguity, and fears of ruin that undermine the anthropologist’s sense of autonomy. Making his way through Naples’s spectacular historic center and outer slums, on the trail of charmingly evasive neomelodici singers and unsettlingly elusive camorristi, Pine himself becomes a music video director and falls into the orbit of a shadowy music promoter who may or may not be a camorra affiliate.

Pine’s trenchant observations and his own improvised attempts at “making do” provide a fascinating look into the lives of people in the gray zones where organized crime blends into ordinary life.

"The historical aspect of this book is splendid, but where it excels is in its fearless and thought-provoking critical judgements. . . . it will lead both beginners and experts to new joys."—David Ekserdjian, Times Literary Supplement

In the first extended sociopolitical interpretation in English of this important group, Albert Boime places the Macchiaioli in the cultural context of the Risorgimento—the political movement that unified Italy, freed from foreign rule, under a secular, constitutional government. Anglo-American art criticism has generally neglected these painters (probably because of their overt political affiliation and nationalist expression), but Boime shows that these artists, while deeply political, nevertheless created aesthetically superior work.

Boime's study departs from previous research on the Macchiaioli by systematically investigating the group's writings, sources, and patronage in relation to the Risogimento. The book also examines both contemporary and later critical responses, revealing how French art criticism has obscured the achievements of Macchiaioli art. Richly illustrated, The Art of the Macchia and the Risorgimento will appeal to anyone interested in nineteenth-century European art or the history of Italy.

McLean scrutinized thousands of letters to and from Renaissance Florentines. He describes the social protocols the letters reveal, paying particular attention to the means by which Florentines crafted credible presentations of themselves. The letters, McLean contends, testify to the development not only of new forms of self-presentation but also of a new kind of self to be presented: an emergent, “modern” conception of self as an autonomous agent. They also bring to the fore the importance that their writers attached to concepts of honor, and the ways that they perceived themselves in relation to the Florentine state.

Tracing the evolution of the Italian avant-garde’s pioneering experiments with art and technology and their subversion of freedom and control

In postwar Italy, a group of visionary artists used emergent computer technologies as both tools of artistic production and a means to reconceptualize the dynamic interrelation between individual freedom and collectivity. Working contrary to assumptions that the rigid, structural nature of programming limits subjectivity, this book traces the multifaceted practices of these groundbreaking artists and their conviction that technology could provide the conditions for a liberated social life.

Situating their developments within the context of the Cold War and the ensuing crisis among the Italian left, Arte Programmata describes how Italy’s distinctive political climate fueled the group’s engagement with computers, cybernetics, and information theory. Creating a broad range of immersive environments, kinetic sculptures, domestic home goods, and other multimedia art and design works, artists such as Bruno Munari, Enzo Mari, and others looked to the conceptual frameworks provided by this new technology to envision a way out of the ideological impasses of the age.

Showcasing the ingenuity of Italy’s earliest computer-based art, this study highlights its distinguishing characteristics while also exploring concurrent developments across the globe. Centered on the relationships between art, technology, and politics, Arte Programmata considers an important antecedent to the digital age.

Artemisia Gentileschi is by far the most famous woman artist of the premodern era. Her art addressed issues that resonate today, such as sexual violence and women’s problematic relationship to political power. Her powerful paintings with vigorous female protagonists chime with modern audiences, and she is celebrated by feminist critics and scholars.

This book breaks new ground by placing Gentileschi in the context of women’s political history. Mary D. Garrard, noted Gentileschi scholar, shows that the artist most likely knew or knew about contemporary writers such as the Venetian feminists Lucrezia Marinella and Arcangela Tarabotti. She discusses recently discovered paintings, offers fresh perspectives on known works, and examines the artist anew in the context of feminist history. This beautifully illustrated book gives for the first time a full portrait of a strong woman artist who fought back through her art.

Between the end of the nineteenth century and over the first half of the twentieth, Italy invaded and occupied the Horn of Africa, Libya, and several other territories. Yet recognition of this history of colonial destruction, racist violence, and genocidal aerial and chemical warfare—carried out not only during the Fascist dictatorship but also under preceding liberal governments—has been consistently repressed beneath the myth that the Italians never truly practiced colonialism.

The late journalist, historian, novelist, campaigner, and former Resistance fighter Angelo Del Boca dismantles this myth. He expertly narrates episodes of state violence committed by Italians both abroad—from Ethiopia to Slovenia, from China to Libya—and “at home” during the civil war following Unification in the 1860s or when the anti-Fascist Resistance faced off against the Republic of Salò after 1943. Attentive to the losses and pain suffered by all sides in war, Del Boca deftly demonstrates how such violence was not only a tool of domination but has also been central to creating and shaping an Italian “people.”

Drawing on a lifetime of interviews as a special correspondent, decades of work in private and state archives, and his own experiences during the Second World War, Del Boca’s popular and influential work has contributed to overturning views of Italian history. Presenting many historical episodes in English for the first time, As Cruel as Anyone Else provides a key to reading contemporary Italy, its place in international politics, and the disturbing permanence of the far-right within mainstream Italian politics.

Nunzio Pernicone and Fraser M. Ottanelli dig into the transnational experiences and the historical, social, cultural, and political conditions behind the phenomenon of anarchist violence in Italy. Looking at political assassinations in the 1890s, they illuminate the public effort to equate anarchy's goals with violent overthrow. Throughout, Pernicone and Ottanelli combine a cutting-edge synthesis of the intellectual origins, milieu, and nature of Italian anarchist violence with vivid portraits of its major players and their still-misunderstood movement.

A bold challenge to conventional thinking, Assassins against the Old Order demolishes a century of myths surrounding anarchist violence and its practitioners.

Thousands of Greek painted vases have emerged from excavations of tombs, sanctuaries, and settlements throughout Etruria, from southern coastal centers to northern communities in the Po Valley. Using documented archaeological assemblages, especially from tombs in southern Etruria, Bundrick challenges the widely held assumption that Etruscans were hellenized through Greek imports. She marshals evidence to show that Etruscan consumers purposefully selected figured pottery that harmonized with their own local needs and customs, so much so that the vases are better described as etruscanized. Athenian ceramic workers, she contends, learned from traders which shapes and imagery sold best to the Etruscans and employed a variety of strategies to maximize artistry, output, and profit.

Born in 1609 into an artisan family, Cecilia Ferrazzi wanted to become a nun. When her parents' death in the plague of 1630 made it financially impossible for her to enter the convent, she refused to marry and as a single laywoman set out in pursuit of holiness. Eventually she improvised a vocation: running houses of refuge for "girls in danger," young women at risk of being lured into prostitution.

Ferrazzi's frequent visions persuaded her, as well as some clerics and acquaintances among the Venetian elite, that she was on the right track. The socially valuable service she was providing enhanced this impresssion. Not everyone, however, was convinced that she was a genuine favorite of God. In 1664 she was denounced to the Inquisition.

The Inquisition convicted Ferrazzi of the pretense of sanctity. Yet her autobiographical act permits us to see in vivid detail both the opportunities and the obstacles presented to seventeenth-century women.

They envisioned a brave new world, and what they got was fascism. As vibrant as its counterparts in Paris, Munich, and Milan, the avant-garde of Florence rose on a wave of artistic, political, and social idealism that swept the world with the arrival of the twentieth century. How the movement flourished in its first heady years, only to flounder in the bloody wake of World War I, is a fascinating story, told here for the first time. It is the history of a whole generation’s extraordinary promise—and equally extraordinary failure.

The “decadentism” of D’Annunzio, the philosophical ideals of Croce and Gentile, the politics of Italian socialism: all these strains flowed together to buoy the emerging avant-garde in Florence. Walter Adamson shows us the young artists and writers caught up in the intellectual ferment of their time, among them the poet Giovanni Papini, the painter Ardengo Soffici, and the cultural critic Giuseppe Prezzolini. He depicts a generation rejecting provincialism, seeking spiritual freedom in Paris, and ultimately blending the modernist style found there with their own sense of toscanità or “being Tuscan.”

In their journals—Leonardo, La Voce, Lacerba, and L’Italia futurista—and in their cafe life at the Giubbe Rosse, we see the avant-garde of Florence as citizens of an intellectual world peopled by the likes of Picasso, Bergson, Sorel, Unamuno, Pareto, Weininger, and William James. We witness their mounting commitment to the ideals of regenerative violence and watch their existence become increasingly frenzied as war approaches. Finally, Adamson shows us the ultimate betrayal of the movement’s aspirations as its cultural politics help catapult Italy into war and prepare the way for Mussolini’s rise to power.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press