39 start with A start with A

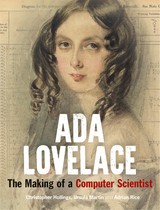

Although it was an unusual pursuit for women at the time, Ada Lovelace studied science and mathematics from a young age. This book uses previously unpublished archival material to explore her precocious childhood—from her curiosity about the science of rainbows to her design for a steam-powered flying horse—as well as her ambitious young adulthood. Active in Victorian London’s social and scientific elite alongside Mary Somerville, Michael Faraday, and Charles Dickens, Ada Lovelace became fascinated by the computing machines of Charles Babbage, whose ambitious, unbuilt invention known as the “Analytical Engine” inspired Lovelace to devise a table of mathematical formulae which many now refer to as the “first program.”

Ada Lovelace died at just thirty-six, but her work strikes a chord to this day, offering clear explanations of the principles of computing, and exploring ideas about computer music and artificial intelligence that have been realized in modern digital computers. Featuring detailed illustrations of the “first program” alongside mathematical models, correspondence, and contemporary images, this book shows how Ada Lovelace, with astonishing prescience, first investigated the key mathematical questions behind the principles of modern computing.

These days, so much of our lives takes place online—but what about our afterlives? Thanks to the digital trails that we leave behind, our identities can now be reconstructed after our death. In fact, AI technology is already enabling us to “interact” with the departed. Sooner than we think, the dead will outnumber the living on Facebook. In this thought-provoking book, Carl Öhman explores the increasingly urgent question of what we should do with all this data and whether our digital afterlives are really our own—and if not, who should have the right to decide what happens to our data.

The stakes could hardly be higher. In the next thirty years alone, about two billion people will die. Those of us who remain will inherit the digital remains of an entire generation of humanity—the first digital citizens. Whoever ends up controlling these archives will also effectively control future access to our collective digital past, and this power will have vast political consequences. The fate of our digital remains should be of concern to everyone—past, present, and future. Rising to these challenges, Öhman explains, will require a collective reshaping of our economic and technical systems to reflect more than just the monetary value of digital remains.

As we stand before a period of deep civilizational change, The Afterlife of Data will be an essential guide to understanding why and how we as a human race must gain control of our collective digital past—before it is too late.

Making arrowheads, blades, and other stone tools was once a survival skill and is still a craft practiced by thousands of flintknappers around the world. In the United States, knappers gather at regional "knap-ins" to socialize, exchange ideas and material, buy and sell both equipment and knapped art, and make stone tools in the company of others. In between these gatherings, the knapping community stays connected through newsletters and the Internet.

In this book, avid knapper and professional anthropologist John Whittaker offers an insider's view of the knapping community. He explores why stone tools attract modern people and what making them means to those who pursue this art. He describes how new members are incorporated into the knapping community, how novices learn the techniques of knapping and find their roles within the group, how the community is structured, and how ethics, rules, and beliefs about knapping are developed and transmitted. He also explains how the practice of knapping relates to professional archaeology, the trade in modern replicas of stone tools, and the forgery of artifacts. Whittaker's book thus documents a fascinating subculture of American life and introduces the wider public to an ancient and still rewarding craft.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, two British inventors, Arthur Pollen and Harold Isherwood, became fascinated by a major military question: how to aim the big guns of battleships. These warships—of enormous geopolitical import before the advent of intercontinental missiles or drones—had to shoot in poor light and choppy seas at distant moving targets, conditions that impeded accurate gunfire. Seeing the need to account for a plethora of variables, Pollen and Isherwood built an integrated system for gathering data, calculating predictions, and transmitting the results to the gunners. At the heart of their invention was the most advanced analog computer of the day, a technological breakthrough that anticipated the famous Norden bombsight of World War II, the inertial guidance systems of nuclear missiles, and the networked “smart” systems that dominate combat today. Recognizing the value of Pollen and Isherwood’s invention, the British Royal Navy and the United States Navy pirated it, one after the other. When the inventors sued, both the British and US governments invoked secrecy, citing national security concerns.

Drawing on a wealth of archival evidence, Analog Superpowers analyzes these and related legal battles over naval technology, exploring how national defense tested the two countries’ commitment to individual rights and the free market. Katherine C. Epstein deftly sets out Pollen’s and Isherwood’s pioneering achievements, the patent questions raised, the geopolitical rivalry between Britain and the United States, and the legal precedents each country developed to control military tools built by private contractors.

Epstein’s account reveals that long before the US national security state sought to restrict information about atomic energy, it was already embroiled in another contest between innovation and secrecy. The America portrayed in this sweeping and accessible history isn’t yet a global hegemon but a rising superpower ready to acquire foreign technology by fair means or foul—much as it accuses China of doing today.

A gripping history that spans law, international affairs, and top-secret technology to unmask the tension between intellectual property rights and national security.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, two British inventors, Arthur Pollen and Harold Isherwood, became fascinated by a major military question: how to aim the big guns of battleships. These warships—of enormous geopolitical import before the advent of intercontinental missiles or drones—had to shoot in poor light and choppy seas at distant moving targets, conditions that impeded accurate gunfire. Seeing the need to account for a plethora of variables, Pollen and Isherwood built an integrated system for gathering data, calculating predictions, and transmitting the results to the gunners. At the heart of their invention was the most advanced analog computer of the day, a technological breakthrough that anticipated the famous Norden bombsight of World War II, the inertial guidance systems of nuclear missiles, and the networked “smart” systems that dominate combat today. Recognizing the value of Pollen and Isherwood’s invention, the British Royal Navy and the United States Navy pirated it, one after the other. When the inventors sued, both the British and US governments invoked secrecy, citing national security concerns.

Drawing on a wealth of archival evidence, Analog Superpowers analyzes these and related legal battles over naval technology, exploring how national defense tested the two countries’ commitment to individual rights and the free market. Katherine C. Epstein deftly sets out Pollen’s and Isherwood’s pioneering achievements, the patent questions raised, the geopolitical rivalry between Britain and the United States, and the legal precedents each country developed to control military tools built by private contractors.

Epstein’s account reveals that long before the US national security state sought to restrict information about atomic energy, it was already embroiled in another contest between innovation and secrecy. The America portrayed in this sweeping and accessible history isn’t yet a global hegemon but a rising superpower ready to acquire foreign technology by fair means or foul—much as it accuses China of doing today.

An audacious, interdisciplinary study that combines the burgeoning fields of digital aesthetics and eco-criticism

In Animal, Vegetable, Digital, Elizabeth Swanstrom makes a confident and spirited argument for the use of digital art in support of ameliorating human engagement with the environment and suggests a four-part framework for analyzing and discussing such applications.

Through close readings of a panoply of texts, artworks, and cultural artifacts, Swanstrom demonstrates that the division popular culture has for decades observed between nature and technology is artificial. Not only is digital technology not necessarily a brick in the road to a dystopian future of environmental disaster, but digital art forms can be a revivifying bridge that returns people to a more immediate relationship to nature as well as their own embodied selves.

To analyze and understand the intersection of digital art and nature, Animal, Vegetable, Digital explores four aesthetic techniques: coding, collapsing, corresponding, and conserving. “Coding” denotes the way artists use operational computer code to blur distinctions between the reader and text, and, hence, the world. Inviting a fluid conception of the boundary between human and technology, “collapsing” voids simplistic assumptions about the human body’s innate perimeter. The process of translation between natural and human-readable signs that enables communication is described as “corresponding.” “Conserving” is the application of digital art by artists to democratize large- and small-scale preservation efforts.

A fascinating synthesis of literary criticism, communications and journalism, science and technology, and rhetoric that draws on such disparate phenomena as simulated environments, video games, and popular culture, Animal, Vegetable, Digital posits that partnerships between digital aesthetics and environmental criticism are possible that reconnect humankind to nature and reaffirm its kinship with other living and nonliving things.

Markets run on information. Buyers make decisions by relying on their knowledge of the products available, and sellers decide what to produce based on their understanding of what buyers want. But the distribution of market information has changed, as consumers increasingly turn to sources that act as intermediaries for information—companies like Yelp and Google. Antitrust Law in the New Economy considers a wide range of problems that arise around one aspect of information in the marketplace: its quality.

Sellers now have the ability and motivation to distort the truth about their products when they make data available to intermediaries. And intermediaries, in turn, have their own incentives to skew the facts they provide to buyers, both to benefit advertisers and to gain advantages over their competition. Consumer protection law is poorly suited for these problems in the information economy. Antitrust law, designed to regulate powerful firms and prevent collusion among producers, is a better choice. But the current application of antitrust law pays little attention to information quality.

Mark Patterson discusses a range of ways in which data can be manipulated for competitive advantage and exploitation of consumers (as happened in the LIBOR scandal), and he considers novel issues like “confusopoly” and sellers’ use of consumers’ personal information in direct selling. Antitrust law can and should be adapted for the information economy, Patterson argues, and he shows how courts can apply antitrust to address today’s problems.

An engrossing origin story for the personal computer—showing how the Apple II’s software helped a machine transcend from hobbyists’ plaything to essential home appliance.

Skip the iPhone, the iPod, and the Macintosh. If you want to understand how Apple Inc. became an industry behemoth, look no further than the 1977 Apple II. Designed by the brilliant engineer Steve Wozniak and hustled into the marketplace by his Apple cofounder Steve Jobs, the Apple II became one of the most prominent personal computers of this dawning industry.

The Apple II was a versatile piece of hardware, but its most compelling story isn’t found in the feat of its engineering, the personalities of Apple’s founders, or the way it set the stage for the company’s multibillion-dollar future. Instead, historian Laine Nooney shows, what made the Apple II iconic was its software. In software, we discover the material reasons people bought computers. Not to hack, but to play. Not to code, but to calculate. Not to program, but to print. The story of personal computing in the United States is not about the evolution of hackers—it’s about the rise of everyday users.

Recounting a constellation of software creation stories, Nooney offers a new understanding of how the hobbyists’ microcomputers of the 1970s became the personal computer we know today. From iconic software products like VisiCalc and The Print Shop to historic games like Mystery House and Snooper Troops to long-forgotten disk-cracking utilities, The Apple II Age offers an unprecedented look at the people, the industry, and the money that built the microcomputing milieu—and why so much of it converged around the pioneering Apple II.

A material history of haptics technology that raises new questions about the relationship between touch and media

Since the rise of radio and television, we have lived in an era defined increasingly by the electronic circulation of images and sounds. But the flood of new computing technologies known as haptic interfaces—which use electricity, vibration, and force feedback to stimulate the sense of touch—offering an alternative way of mediating and experiencing reality.

In Archaeologies of Touch, David Parisi offers the first full history of these increasingly vital technologies, showing how the efforts of scientists and engineers over the past three hundred years have gradually remade and redefined our sense of touch. Through lively analyses of electrical machines, videogames, sex toys, sensory substitution systems, robotics, and human–computer interfaces, Parisi shows how the materiality of touch technologies has been shaped by attempts to transform humans into more efficient processors of information.

With haptics becoming ever more central to emerging virtual-reality platforms (immersive bodysuits loaded with touch-stimulating actuators), wearable computers (haptic messaging systems like the Apple Watch’s Taptic Engine), and smartphones (vibrations that emulate the feel of buttons and onscreen objects), Archaeologies of Touch offers a timely and provocative engagement with the long history of touch technology that helps us confront and question the power relations underpinning the project of giving touch its own set of technical media.

We are now living in the richest age of public memory. From museums and memorials to the vast digital infrastructure of the internet, access to the past is only a click away. Even so, the methods and technologies created by scientists, espionage agencies, and information management coders and programmers have drastically delimited the ways that communities across the globe remember and forget our wealth of retrievable knowledge.

In Architects of Memory: Information and Rhetoric in a Networked Archival Age, Nathan R. Johnson charts turning points where concepts of memory became durable in new computational technologies and modern memory infrastructures took hold. He works through both familiar and esoteric memory technologies—from the card catalog to the book cart to Zatocoding and keyword indexing—as he delineates histories of librarianship and information science and provides a working vocabulary for understanding rhetoric’s role in contemporary memory practices.

This volume draws upon the twin concepts of memory infrastructure and mnemonic technê to illuminate the seemingly opaque wall of mundane algorithmic techniques that determine what is worth remembering and what should be forgotten. Each chapter highlights a conflict in the development of twentieth-century librarianship and its rapidly evolving competitor, the discipline of information science. As these two disciplines progressed, they contributed practical techniques and technologies for making sense of explosive scientific advancement in the wake of World War II. Taming postwar science became part and parcel of practices and information technologies that undergird uncountable modern communication systems, including search engines, algorithms, and databases for nearly every national clearinghouse of the twenty-first century.

The Art, Science, and Magic of the Data Curation Network: A Retrospective on Cross Institutional Collaboration captures the results of a project retrospective meeting and describes the necessary components of the DCN’s sustained collaboration in the hopes that the insights will be of use to other collaborative efforts. In particular, the authors describe the successes of the community and challenges of launching a cross-institutional network. Additionally, this publication details the administrative, tool-based, and trust-based structures necessary for establishing this community, the “radical collaboration” that is the cornerstone of the DCN, and potential future collaborations to address shared challenges in libraries and research data management. This in-depth case study provides an overview of the critical work of launching a collaborative network and transitioning to sustainability. This publication will be of special interest to research librarians, data curators, and anyone interested in academic community building.

This volume develops from the studies published in Roy Ascott's highly successful Reframing Consciousness, documenting the very latest research from those connected with the CAiiA-STAR centre and its associated conferences. Their work embodies artistic and theoretical research in new media and telematics including aspects of artificial life, robotics, technoetics, performance, computer music and intelligent architecture, to growing international acclaim.

Tracing the evolution of the Italian avant-garde’s pioneering experiments with art and technology and their subversion of freedom and control

In postwar Italy, a group of visionary artists used emergent computer technologies as both tools of artistic production and a means to reconceptualize the dynamic interrelation between individual freedom and collectivity. Working contrary to assumptions that the rigid, structural nature of programming limits subjectivity, this book traces the multifaceted practices of these groundbreaking artists and their conviction that technology could provide the conditions for a liberated social life.

Situating their developments within the context of the Cold War and the ensuing crisis among the Italian left, Arte Programmata describes how Italy’s distinctive political climate fueled the group’s engagement with computers, cybernetics, and information theory. Creating a broad range of immersive environments, kinetic sculptures, domestic home goods, and other multimedia art and design works, artists such as Bruno Munari, Enzo Mari, and others looked to the conceptual frameworks provided by this new technology to envision a way out of the ideological impasses of the age.

Showcasing the ingenuity of Italy’s earliest computer-based art, this study highlights its distinguishing characteristics while also exploring concurrent developments across the globe. Centered on the relationships between art, technology, and politics, Arte Programmata considers an important antecedent to the digital age.

We imagine that we are both in control of and controlled by our bodies—autonomous and yet automatic. This entanglement, according to David W. Bates, emerged in the seventeenth century when humans first built and compared themselves with machines. Reading varied thinkers from Descartes to Kant to Turing, Bates reveals how time and time again technological developments offered new ways to imagine how the body’s automaticity worked alongside the mind’s autonomy. Tracing these evolving lines of thought, An Artificial History of Natural Intelligence offers a new theorization of the human as a being that is dependent on technology and produces itself as an artificial automaton without a natural, outside origin.

From hidden connections in big data to bots spreading fake news, journalism is increasingly computer-generated. An expert in computer science and media explains the present and future of a world in which news is created by algorithm.

Amid the push for self-driving cars and the roboticization of industrial economies, automation has proven one of the biggest news stories of our time. Yet the wide-scale automation of the news itself has largely escaped attention. In this lively exposé of that rapidly shifting terrain, Nicholas Diakopoulos focuses on the people who tell the stories—increasingly with the help of computer algorithms that are fundamentally changing the creation, dissemination, and reception of the news.

Diakopoulos reveals how machine learning and data mining have transformed investigative journalism. Newsbots converse with social media audiences, distributing stories and receiving feedback. Online media has become a platform for A/B testing of content, helping journalists to better understand what moves audiences. Algorithms can even draft certain kinds of stories. These techniques enable media organizations to take advantage of experiments and economies of scale, enhancing the sustainability of the fourth estate. But they also place pressure on editorial decision-making, because they allow journalists to produce more stories, sometimes better ones, but rarely both.

Automating the News responds to hype and fears surrounding journalistic algorithms by exploring the human influence embedded in automation. Though the effects of automation are deep, Diakopoulos shows that journalists are at little risk of being displaced. With algorithms at their fingertips, they may work differently and tell different stories than they otherwise would, but their values remain the driving force behind the news. The human–algorithm hybrid thus emerges as the latest embodiment of an age-old tension between commercial imperatives and journalistic principles.

Automating technologies threaten to usher in a workless future. But this can be a good thing—if we play our cards right.

Human obsolescence is imminent. The factories of the future will be dark, staffed by armies of tireless robots. The hospitals of the future will have fewer doctors, depending instead on cloud-based AI to diagnose patients and recommend treatments. The homes of the future will anticipate our wants and needs and provide all the entertainment, food, and distraction we could ever desire.

To many, this is a depressing prognosis, an image of civilization replaced by its machines. But what if an automated future is something to be welcomed rather than feared? Work is a source of misery and oppression for most people, so shouldn’t we do what we can to hasten its demise? Automation and Utopia makes the case for a world in which, free from need or want, we can spend our time inventing and playing games and exploring virtual realities that are more deeply engaging and absorbing than any we have experienced before, allowing us to achieve idealized forms of human flourishing.

The idea that we should “give up” and retreat to the virtual may seem shocking, even distasteful. But John Danaher urges us to embrace the possibilities of this new existence. The rise of automating technologies presents a utopian moment for humankind, providing both the motive and the means to build a better future.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press