eISBN: 978-0-8262-6209-7 | Cloth: 978-0-8262-1221-4

Library of Congress Classification PR5438.W48 1999

Dewey Decimal Classification 821.7

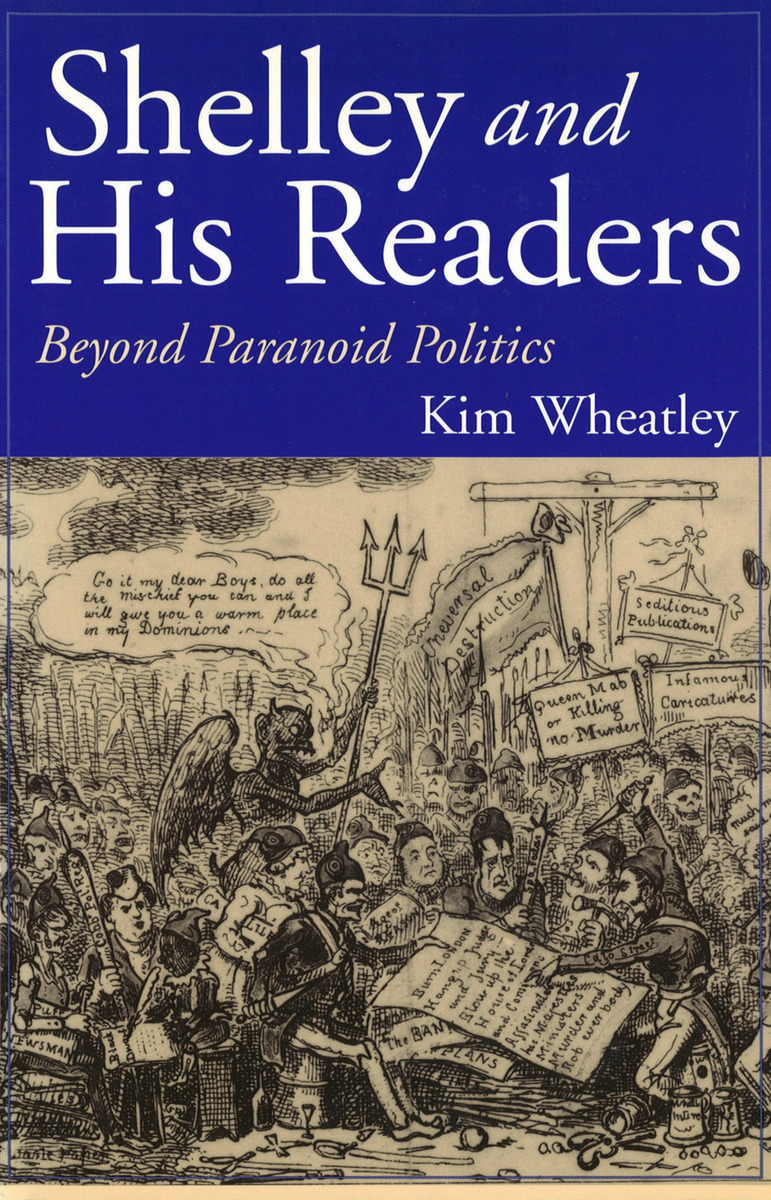

In Shelley and His Readers, the first full-length critical analysis of the dialogue between Shelley's poetry and its contemporary reviewers, Kim Wheatley argues that Shelley's idealism can be recovered through the study of his poetry's reception. Incorporating extensive research in major early-nineteenth-century British periodicals, Wheatley integrates a reception-based methodology with careful textual analysis to demonstrate that the early reception of Shelley's work registers the immediate impact of the poet's increasingly idealistic passion for reforming the world.

Wheatley examines Shelley's poetry within the context of Romantic-era "paranoid politics," a simultaneously empowering and disabling dynamic in which the reviewers employ a heightened language of defensiveness and persecution that paints their adversaries as Satanic rebels against orthodoxy. This "paranoid style" displays a preoccupation with the efficacy of the printed word and singles out radical writers such as Shelley as sources of social contamination.

Using Shelley's Queen Mab to illustrate his early radicalism, Wheatley demonstrates that the poet, like his contemporary reviewers, is caught up in paranoid rhetoric. Failing to challenge the assumptions underlying the paranoid style-conspiracy and contagion-in this poem Shelley takes merely a defiant, oppositional stance. However, Shelley's later poems, exemplified by Prometheus Unbound and Adonais, circumvent the reviewers' rhetoric through their boldly experimental language, a process registered by the reviewers' own responses. These less explicitly political poems transcend the dynamics of cultural paranoia by shifting to an apolitical conception of the aesthetic. In collaboration with its early readers, Shelley's poetry thus moves momentarily beyond paranoid politics.

The final chapter of this study argues that the posthumous reception of Adonais uniquely replicates the elegiac moves and complex idealism of the poem, concluding with a discussion of how the Shelley circle aestheticized the poet after his death.

Shelley and His Readers offers a new approach to the question of how to recuperate Romantic idealism in the face of challenges from both deconstructive and historicist criticism. Its innovative use of reception-based analysis will make this book invaluable not only to specialists of the Romantic period but also to anyone interested in new developments in literary criticism.

See other books on: 1792-1822 | Authors and readers | Politics and literature | Shelley | Shelley, Percy Bysshe

See other titles from University of Missouri Press